What is it?

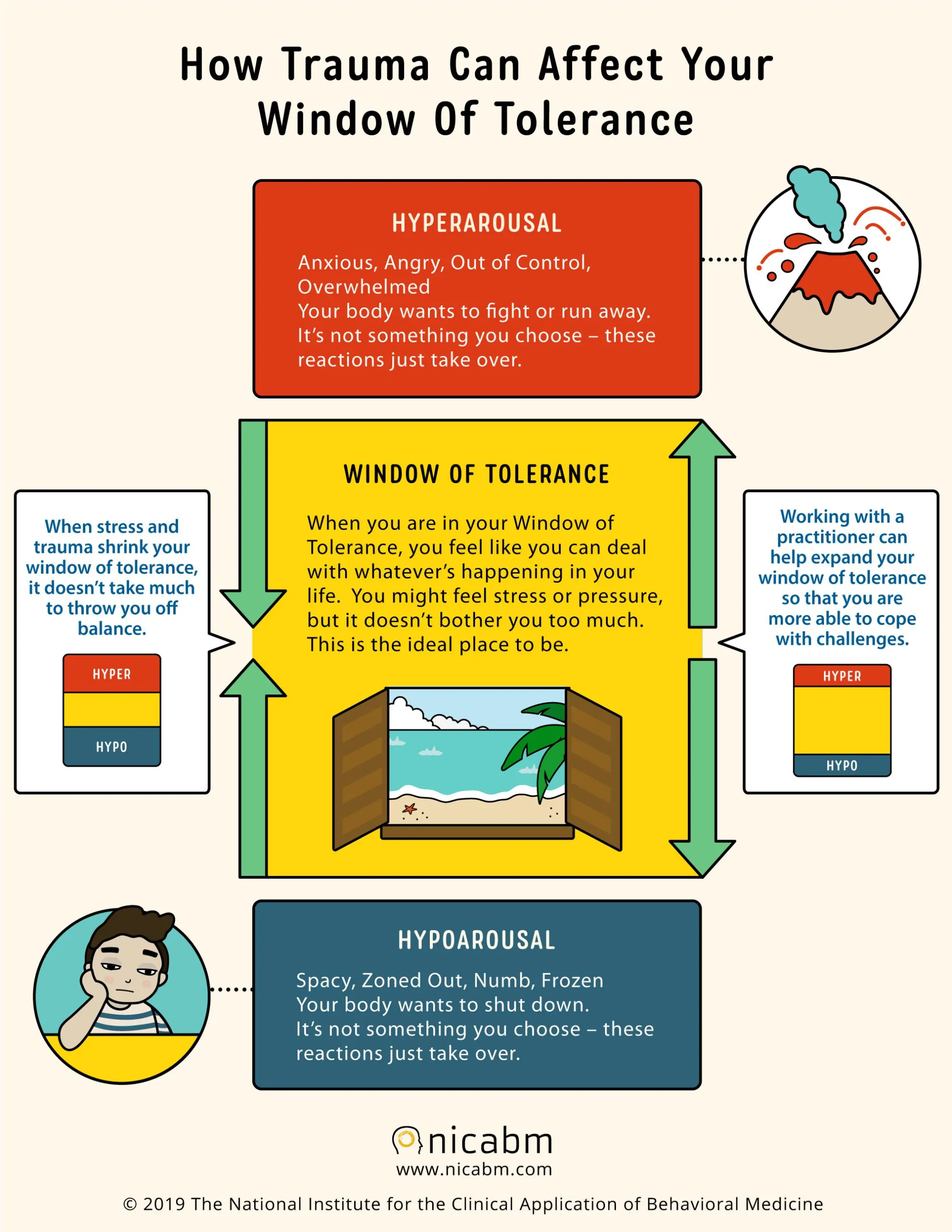

Our Window of Tolerance is a state of mind where we are successfully regulating our emotions. To much regulation, and we feel detached or we may even disassociate. Too little regulation and we lose our temper or we run away. It’s a place where we are just anxious enough to make decisions and think clearly.

Our brains are wired to react to perceived threats. This is evolutionary, and enables us to react in that fight-or-flight place. Which is fine when our main aim in life was to find food and shelter without being eaten ourselves. However in modern society, threats come not so much from outside as they do from our own processing of emotions. Often, what we are anxious about most is feeling shame, hurt, rejection or like we are unworthy or a failure. In the absence of these difficult emotions, we can usually operate very comfortably. However most of us know that some anxieties are easily triggered, revealing hidden traumas that are all part of our early development.

Between anxiety and depression

Our response to anxiety, if it becomes too much, is either to enter the fight-flight zone (hyperarousal) or we go to “freeze”, which is a third state whereby we stay on high alert but we feel as if we are in a bubble, with everything happening around us. We might be aware of depressive feelings involving sadness and a sense of anger which cannot find expression. This is also called “hypoarousal” but the word is so similar to hyperarousal, I tend not to use it.

From NICABM.

The space between fight/flight and freeze is often called our “Window of Tolerance”. Given that hardly a decision can be made without at least a little anxiety, we can tolerate that and can go about our day without being especially concerned about anything. We might even have strategies for staying in that place, which is where “people pleasing” comes in – the hope that if we’re nice to people then they won’t be a threat in return. This is also known as that “fawn” place, using the f-language which has developed around fight-flight.

Tolerating the anxiety

Anxiety can never totally go away. It’s not meant to. But we can help ourselves in many ways. A GP will likely prescribe anti-anxiety medication like diazepam. Or an anti-depressant. But in therapy, we consider the feelings we are most anxious about feeling. Because when we might project our anxiety, e.g. “I am worried our child might fail his exams”, aren’t we really concerned about how it will be for us if that happened? Yes, we want what’s best for the child but being anxious won’t help. What would we feel if he or she fails? Maybe shame, maybe guilt, maybe sadness. Can we, in fact, tolerate these feelings?

It is often the case that we might feel judged in such situations. It’s somehow us that’s failed. Perhaps this triggers feelings we had in relation to our own parents when we were taking exams or doing anything else that had consequences. In the therapy room, we have a chance to explore those feelings in a compassionate way. And eventually to know that these echoes from the past may have served their purpose at the time, but need not threaten us today.

Compassion

The antidote to shame is compassion. Well, to be clear, the opposite to shame is pride. And some approaches will encourage us to be proud of what might be shameful. “Yes, I’m a terrible person, but that’s your problem.” However in many ways, pride is as problematic as shame if our goal is to gain agency in the presence of challenging emotions. Compassion, on the other hand, puts us in the observer role.

Humans are generally not great at self compassion. We’re usually OK when it comes to offering compassion. With the earlier example was might say “It sounds hard for you to see your child fail their exams. Let’s do something nice this afternoon.” But when it comes to ourselves, we feel like we should somehow stay with the shame as if we’re being punished. A whole therapy has built up around this, known as Compassion Focused Therapy. It advocates self-soothing, mindfulness and generally developing our own self-compassion skills.

In the relational way that I prefer to practise, we focus more on allowing shameful thoughts and feelings into the room. If the therapist can accept the feelings, allowing themselves to feel these too, while clearly not disintegrating in the process, then the client can start to tolerate these too. This is essentially what Wilfred Bion called “containment”, which originally referred to the parent-baby relationship but is equally valid in the therapeutic relationship.

Containing overwhelming emotions helps the client regulate rather than avoid or become overwhelmed by them.

Adrian Tupper,

Therapist in Private Practice. 2025.